Discover MAYA

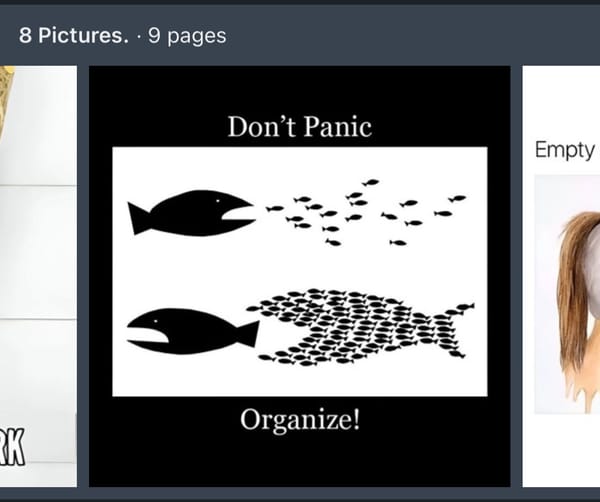

Raymond Loewy’s journey from disappointment to vision laid the foundation for his groundbreaking design philosophy, MAYA: Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable. His approach teaches us how to balance bold innovation with the comfort of familiarity, reshaping the world one design at a time.

Most Advanced Yet Acceptable—maya.

He said to sell something surprising, make it familiar; and to sell something familiar, make it surprising.

Here's the reality, laid bare and unfiltered: 1919. Raymond Loewy, not yet the "father of industrial design," boards the SS France, a battered soul clutching a fragile hope. The influenza pandemic had stolen his parents; his service in the French army, a finished story. At 25, New York City shimmered on the horizon, a beacon promising reinvention, a place to forge a new life as an electrical engineer.

Manhattan’s skyline rose to meet him, a concrete jungle pierced by the neoclassical spire of 120 Broadway. He and his brother, Maximilian, sped towards it, the building’s form a giant tuning fork humming against the sky. Up they soared, forty stories to the observatory, and into a world transformed.

“New York was throbbing at our feet in the crisp autumn light,” Loewy recounted in his 1951 memoir.Picture this: a boundless cityscape pulsing with life, a canvas brimming with potential. But the initial awe quickly faded. The elegant, streamlined metropolis of Loewy's imagination collided with the gritty reality of 1919 Manhattan.

This was a city raw and untamed, a chaotic jumble of clunky architecture, a noisy monument to industry.

"Bulky, noisy, and complicated," he observed, his European sensibilities deeply offended.

The vision of refined beauty he held dear seemed to shatter before his eyes.

From his initial disappointment, a new vision emerged. Loewy possessed a dual sight: he saw Manhattan as it was, gritty and untamed, but also as it could be, a testament to elegant design.

The city was rimming with the potential for transformation. His dream – a world sculpted by sleek, elegant modernity – was about to become something much more tangible.

He would take the unwieldy, bulky forms of the industrial age and refine them, one design at a time.

The future, he declared, would be beautiful.

I put this together, after reading Derek Thomson's article in the The Atlantic Monthly: THE FOUR-LETTER CODE TO SELLING JUST ABOUT ANYTHING